Morning Cultural Content readers 👋

We talk about storytelling a lot in the sector. We’ve all read stories. We all like stories. But how many of us would say they have a solid understanding of how stories work? Why do some stories feel satisfying and some ‘meh’? And how do the rules of storytelling apply to digital content?

This week I’m gleeful to announce Anna Faherty as guest author of this post. She’s recently written a great book Writing Online and Audio Stories with Routledge, which I finished last week and thought was EXCELLENT.

If you’re quick, you can get 20% off Anna’s book with code EFLY01 if you buy direct from Routledge (valid until 30 June).

Anna Faherty is a writer, interpretation developer and trainer who works with cultural and heritage organisations. She’s also a lecturer at London College of Communications. She’s passionate about developing audience-focused content that delivers desired outcomes.

Over to Anna…

How stories work and what that means for content creators

When I got a gig writing one of Wellcome Collection’s first digital stories a decade ago, I was excited by the contract — for a second. Then I panicked. I had plenty of writing experience, but I realised I knew next to nothing about the mechanics of storytelling.

I’m pretty sure I’m not the only person who’s ever struggled with this. Look at numerous ‘our story’ or ‘stories from the collections’ webpages and you’ll soon see that most online text or audio ‘story’ content fails to tell a story.

What even is a story?

To get myself story ready, I buried myself in research, only to keep reading the same mantras: our brains are hard-wired for story…stories help us make sense of the world…stories are memorable, marketable…

Sadly, none of these clichés helped me make much practical sense of what a story actually is or what stories do, particularly in a nonfiction setting.

Today, after collaborating and writing, teaching and writing, researching and writing, I finally understand that the essence of any story is remarkably simple: all stories introduce us to someone facing some kind of challenge and then show us what happens next.

Readers and listeners are drawn into stories because they want to know how that person overcomes that challenge – whether it’s a young Victorian girl who contracted smallpox or how Henry Wellcome found space for his ever-expanding spear collection.

Armed with this understanding of stories, I realised two important things:

Stories about objects don’t have the same emotional impact as stories that revolve around people. If you want to tell an attention-grabbing, emotionally engaging story about a beautiful 18th century vase, you need to tell a story about someone related to it. That might be the maker of the vase, an owner of it, the conservator who repaired it or someone else entirely.

Stories aren’t synonymous with comprehensive histories written for Wikipedia. Stories rarely start by telling you when someone was born. Instead, they focus on a particular challenge that happened to a particular person at a particular time and place.

For some cultural content creators, these two points may prompt new ways of kicking off stories. But even if you have a good opening line, how do you get people to stick around for the rest of the story, when they could be consuming listicles and watching TikTok instead?

The Story Funnel

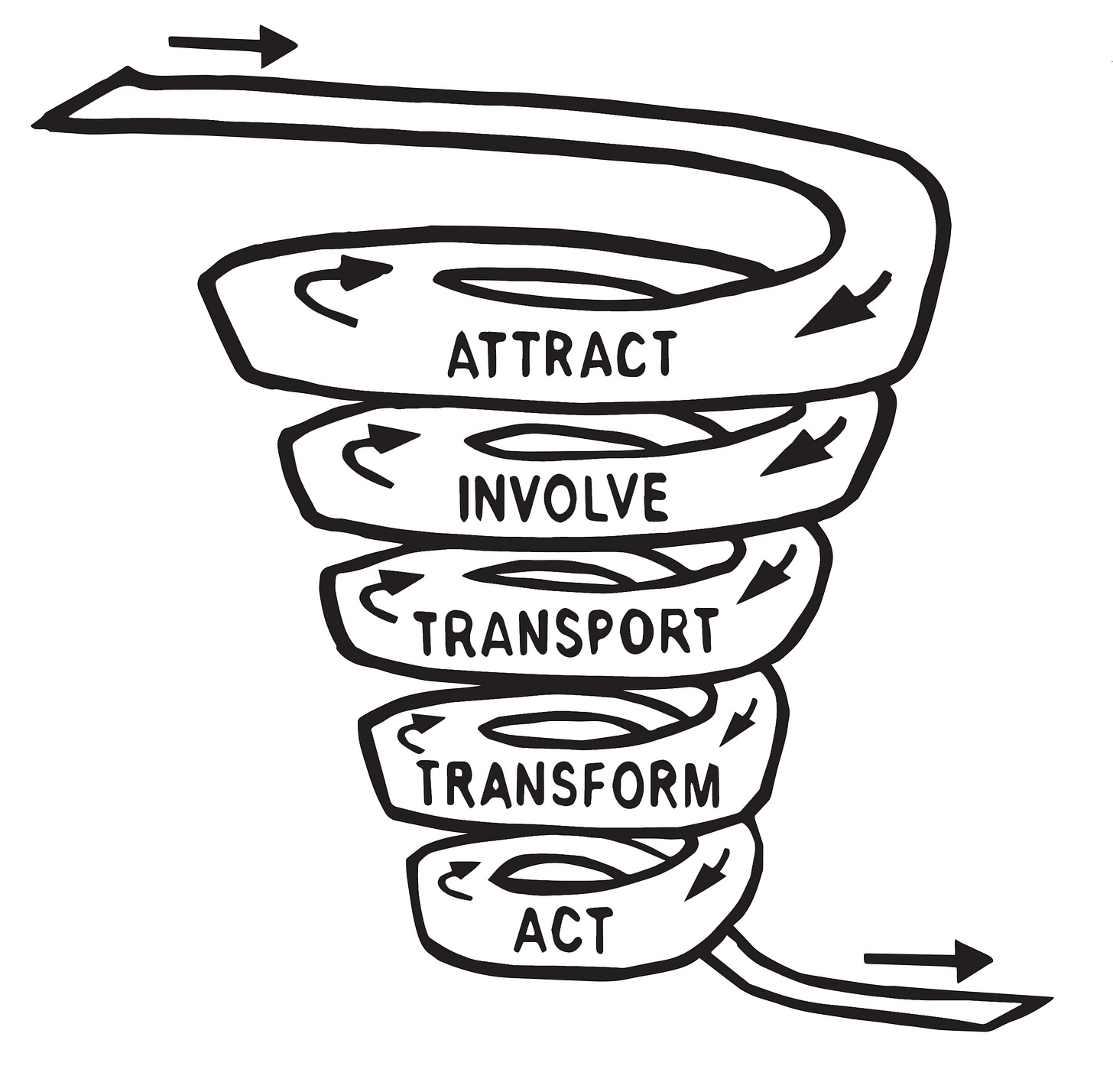

The Story Funnel can help. Based on narrative theory and empirical research, the Story Funnel is a simplified model of what happens when someone reads or listens to a story. It’s a useful tool for understanding how stories work or for constructing and telling stories that keep people with you.

The concept is inspired by the Marketing Funnel, a similar model that illustrates how marketing activities convert a large pool of disinterested strangers into smaller and smaller numbers of engaged purchasers and followers. The Story Funnel, on the other hand, sucks readers or listeners in and pulls them deeper and deeper into the world of the story. It comprises five stages:

Attract

Involve

Transport

Transform

Act

Let’s look at what happens to readers (or listeners) at each stage:

ATTRACT: readers spot a character in trouble and pay attention

As social creatures, humans spend an inordinate amount of time monitoring what other people are thinking and doing. When we’re online and notice someone like us in trouble, or a stranger facing a challenge that resonates, our natural curiosity puts us on alert. We pause or click through because we want to find out more.

INVOLVE: readers imagine what’s going on and become engaged with the story

We become involved in a story because we picture scenes within it and build our own interpretation of events. The same process happens when you watch a couple sitting at a table in a restaurant and imagine what’s going on with them. You create a feasible backstory by combining the cues you’re given with personal knowledge of similar situations. If we identify with the person in the story we root for them and imagine all the ways they might extricate themselves from trouble – like hoping one of the people at the other table gets away from the obstinate bore they appear to be dining with.

TRANSPORT: readers become so involved that they leave the real world behind

When we’re fully immersed in a story we detach from real life. We’re transported into the environment of the story and want to influence what happens, which is why you might find yourself shouting “don’t go into the cellar!” at a character in a horror film. We travel so deeply into this other world that we suspend disbelief and become vulnerable to influence from within the story.

TRANSFORM: readers emerge thinking and feeling differently

Like travelling in real life, travelling into a story opens our minds to alternative ways of thinking and provides new perspectives on the world and ourselves. Numerous research studies show that stories change us. For instance, if you read a story about a holiday destination, you’re more likely to view it favourably than if you read a list of facts about it. If a child listens to a story while in hospital, they’ll view nursing staff more positively – and even feel less physical pain – than if they played a game instead.

ACT: readers do something in light of their story experience

Once you’ve spent time in a story, you’re primed to take action afterwards. In comparison with receiving facts about an issue, reading or listening to a story makes you more likely to subscribe to a newsletter, change your behaviour or donate greater sums of money to a story-related cause. It’s no wonder literary scholar Jonathan Gottschall describes storytelling as ‘witchery’.

10 storytelling tips

You could write a whole book about how to usher readers through each stage of the Story Funnel (as I’ve done…) but the following tips provide quick starting points for writing stories that attract, involve and influence readers and listeners.

Consider your purpose and brand when you choose what story to tell.

People take messages and points of view away from stories. It makes sense for those messages and perspectives to reflect your brand and your organisational goals.Reflect what’s going on in the world and the emotional tone of the moment.

Stories resonate more strongly if they feel familiar — so much so that readers feel more transported into a story about winter when they read it during winter. We also feel more transported when a story’s emotional tone matches our emotional state, which explains why we seek out ‘weepie’ movies when we feel low.Choose a likeable character and a challenge that resonates.

When you’re telling true-life stories, you can’t, of course, concoct the perfect character. You can, however, choose to tell the story from a specific character’s perspective – someone your users will identify with. You might even place your user in the story themselves, as these opening questions from a Migration Museum podcast do: “How far would you travel to find love? Can you imagine crossing the ocean to marry a total stranger?”Introduce your character and challenge as soon as possible.

Grab attention by posing the challenge in the first couple of lines, as this National Archives of Australia story does: “On 23 November 1935, American Lincoln Ellsworth flew across the Antarctic to explore and map new territory. But when arduous conditions and insufficient fuel forced his plane to land, he and his pilot were stranded on a remote base with no way to contact the outside world.”Provide visual and sensory details.

These involve readers and listeners by enabling them to build their own image of where the action takes place and what’s going on. Quotes from first-hand sources often do this well, as this line from a pilot who witnessed a British Nuclear Test, featured in an Avro Heritage Museum podcast, shows: “I can still see the skeleton of my fingers through the hole… when that flash went off”.Leave gaps.

You might recognise this tip under the more familiar guise of ‘show don’t tell’, a maxim that enables readers and listeners to create their own interpretation of events. This extract from an Old Operating Theatre Museum’s interactive story shows us just how unsanitary 19th-century surgery practices were, without explicitly telling us so: “You wipe the knife on your apron and pass it to Furze. He places it back in the velvet-lined box ready for use on the next patient.”Build suspense.

Transport people into the story world by creating uncertainty about whether the character will overcome their challenge. Once you’ve sparked initial curiosity, create a momentary information gap, for instance by stepping away from the action to deliver a nugget of backstory. As the story moves on, maintain uncertainty by holding back key information or narrowing the character’s options.Stay real.

Users are more likely to feel transported if they believe the environment, events and emotions within the story to be real.Resolve the challenge.

Users stick with the story because they want to know what happened — so show them. In true stories, there may not be a neat ‘character overcomes challenge’ moment, but every story needs a resolving endpoint.Drive action.

Offer options to share or comment on the story, or set out more impactful calls to action. To exploit the full witchery of stories, be sure to align these with the story content.

It’s ten years since I began my quest to understand how stories work. I couldn’t have expected then that I’d write a book on the topic. The writing process filled plenty of gaps in my knowledge, but I hope the end product also fills a gap in practical advice about how to tell short-form nonfiction stories in digital contexts. Whether you read it or not, it’s worth remembering that people become involved in stories because they spot another person in trouble. If you can find the trouble and organise the subsequent events to build suspense, you’re well on the way to creating an attention-grabbing story with the power to transport, transform and drive action.