How archiving is adapting to digital creativity

As artists increasingly create digitally, how are archivists re-evaluating what's worth keeping? A guest post from Katrina Rolley, in collaboration with the National Library of Scotland

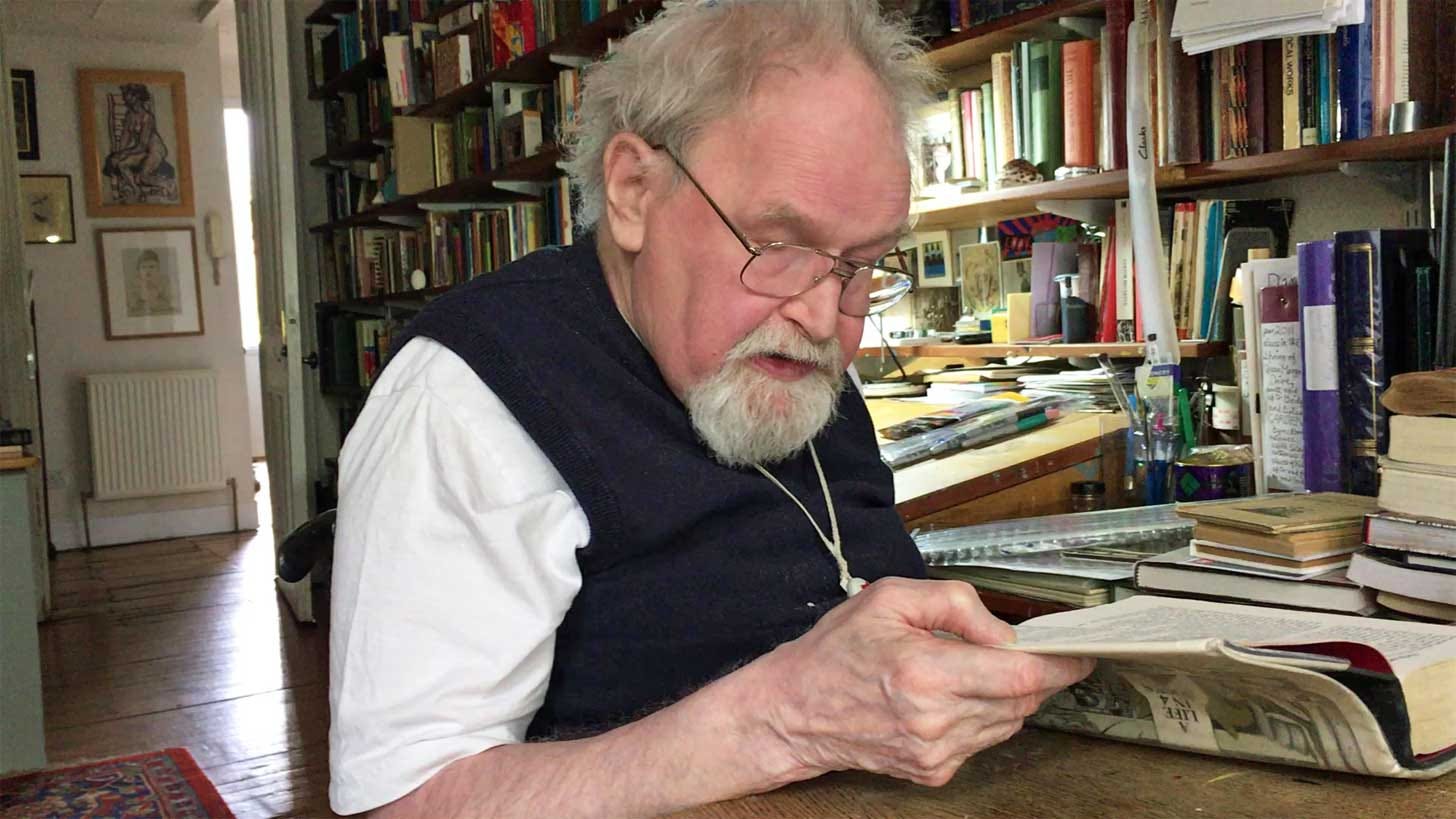

Today, a thought-provoking guest post from Katrina Rolley, the creator of A Gray Space – a collaborative digital project inspired by her uncle, the artist and writer Alasdair Gray. As Katrina considers the implications of preserving her uncle’s analogue work digitally, she speaks to Dr Chris Cassells from the National Library of Scotland about how archiving is evolving in an era when artists increasingly work digitally themselves. What should be kept, and how do we determine what will matter to future generations? Over to Katrina.

When I inherited my dad’s old Amstrad word processor as a student in the 1980s, I quickly became hooked on this new way of working. No more crossings out, corrections and marginal notes. I could change and re-arrange my words as often as I liked and still have perfectly clean copy. Fast forward 40 years and that new technology enables every aspect of our lives. But while A Gray Space is digital-only, it explores the legacy of an analogue creative whose output was the polar opposite of clean copy.

How much would have been lost if my uncle had worked on an iPad or laptop rather than with paint, pencils and paper – and what does it mean for archives like the National Library of Scotland?

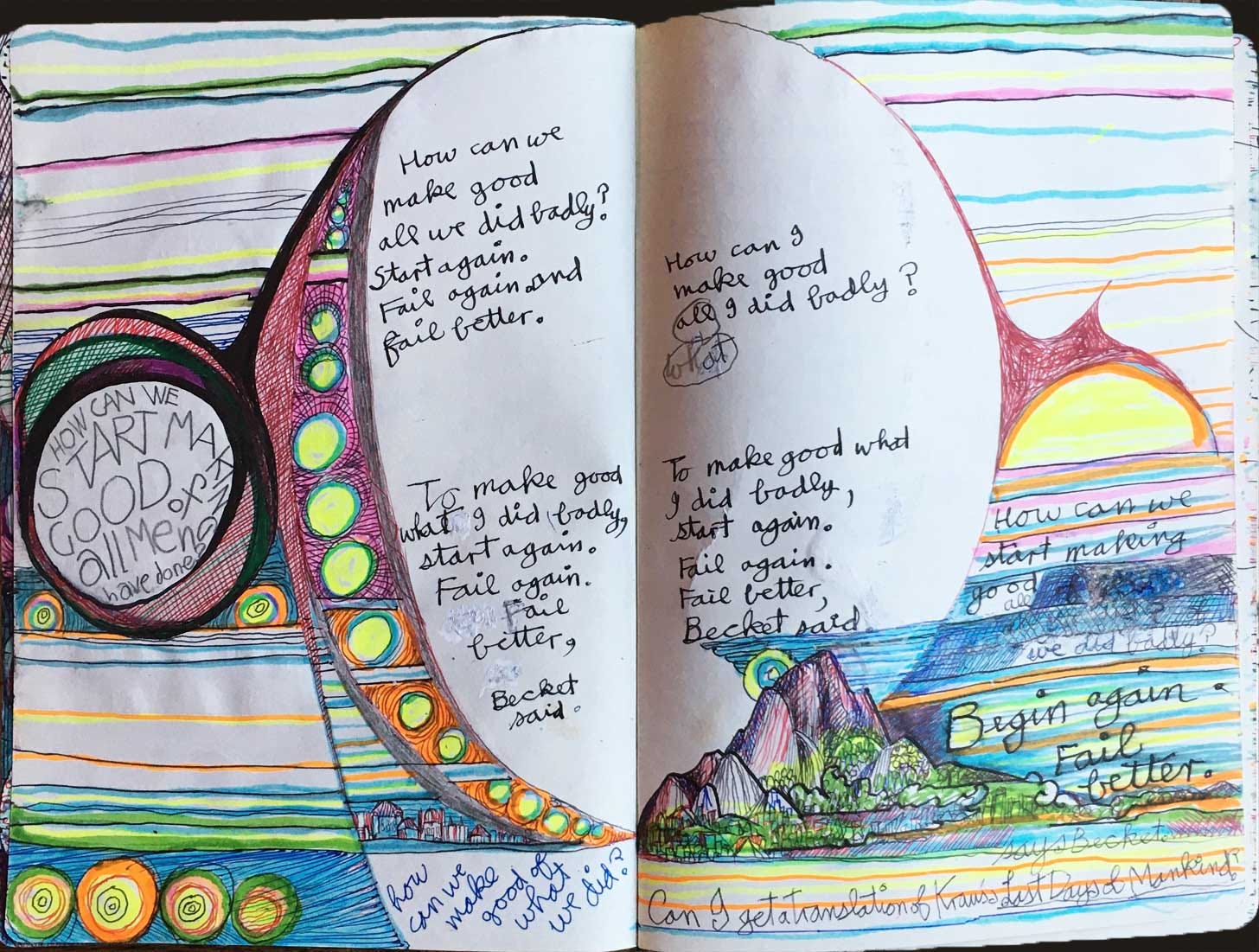

My uncle’s manuscripts and papers are now safely stored in the National Library of Scotland and while his choice of materials is a conservation nightmare, their tangible evidence offers an immediate and powerful connection to Alasdair and his creative process – as we see the movement of his hands while following the ideas that interested him.

So how much would have been lost if my uncle had worked on an iPad or laptop rather than with paint, pencils and paper? Not because we’d failed to preserve the evidence of his creative practice, but because it never existed in the first place. And how are institutions like the NLS responding to the use of digital tools by today’s creatives?

The National Library of Scotland’s approach to digital archiving

I’ve been speaking to Dr Chris Cassells, Head of Archives and Manuscript Collections at the National Library of Scotland about these questions. Talking to Chris provided some answers – but raised many more compelling questions, as we tried to explore our increasingly digital future together.

At the very start of our conversation, Chris explained that enabling as many people as possible to experience a personal connection with the primary sources in their collection, such as Alasdair’s archive, is central to his definition of success. Which immediately highlighted an existential issue – how will we connect to our creative past when the evidence of our endeavours is digital and intangible rather than physical and hand-crafted?

As we spoke, it became clear that Chris and his colleagues are grappling with the same kinds of digital issues faced by many of us in our professional and private lives – but with the heavy responsibility for connecting future generations to our collective past.

The digital volume problem: how much do we preserve?

Notions of scarcity and rarity are implicit in the value of archives, which exist to preserve important documents that might otherwise be lost to us. When materials were expensive and manuscripts created by hand, comparatively small numbers of documents were produced even by prolific creatives like Alasdair. But this foundational aspect of archives is deeply disrupted when contemporary creatives can produce and save multiple versions of their work electronically and the contents of all their digital devices can be downloaded, stored, interrogated and endlessly replicated – with each version being indistinguishable from the original.

This existential shift from scarcity to abundance and the vision of AI tools cataloguing AI-generated artefacts begs the question – do we collect it just because we can?

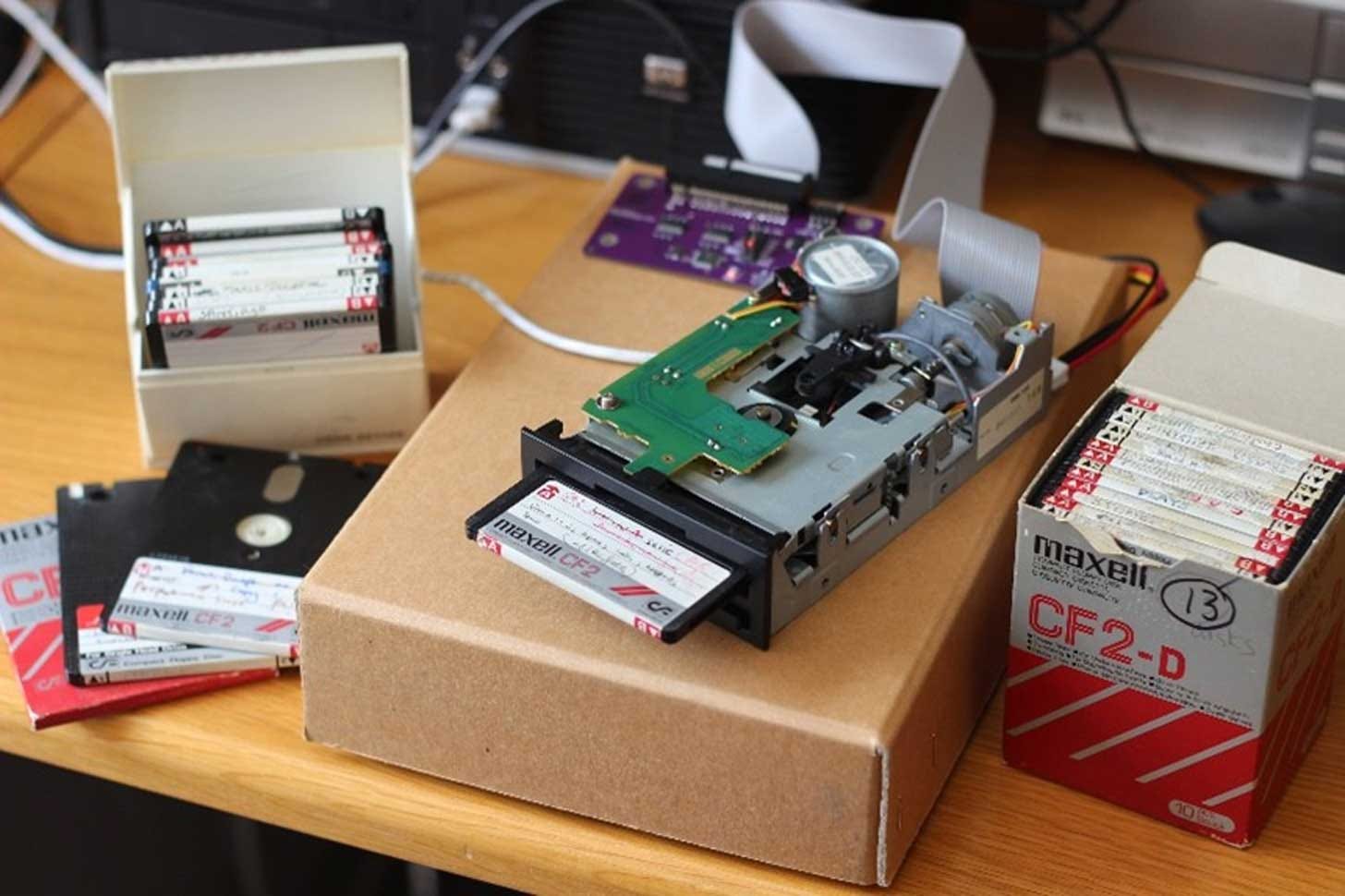

Creatives now give the NLS hard drives, USB drives, laptops and desktop PCs for data extraction and storage and documents are also collected from organisations and individuals via file transfer. Files are copied and stored in at least two different physical locations and the cloud. But as the volume of information being held continues to expand so do the age-old issues of storage capacity, cataloguing and public access.

Digital tools may offer some ways forward but this existential shift from scarcity to abundance and the vision of AI tools cataloguing AI-generated artefacts begs the question – do we collect it just because we can? Or do we need to reconsider legacy collecting practices in an age of information abundance?

How much does the context of the object matter?

Aside from Alasdair’s addiction to Tippex correction fluid, my uncle’s creative tools would be as recognisable to the writers who preceded him as they are to the NLS’s conservators. But the rapid cycles of change in digital tools and technologies present challenges for creatives, curators and conservators alike.

Preserving digital documents in their original format requires money and technical skills. Is the authenticity worth it? How much can we afford to care?

Things have improved since the obsolete software and storage systems of the late ‘90s and early noughties raised the spectre of a ‘digital dark ages’. Standards have emerged to ensure the long-term accessibility of digital documents but technical challenges still exist, along with curatorial questions around context and veracity.

Just as art historians debate the pros and cons of removing altarpieces from their original settings, so archivists now debate what’s lost when documents created using obsolete hardware and software are viewed as PDFs. But preserving and accessing digital documents in their original format and context requires money and technical skills that aren’t available to most archives, and is the authenticity worth it? How far does the medium impact the message? And how much can we afford to care?

In an age of novelty, where will future generations find value?

Connected to these issues of access and obsolescence are concerns about what to collect and where future value will lie in a world that’s constantly encouraged towards the popular and the new.

Writers and other creatives now have multiple ways to develop ideas and generate output. Audio and video are often more easily available than pencil and paper and the lines between process and product are increasingly blurred, in an age when writers need to generate an audience in order to get published.

If you collect a writer’s digital letters and manuscripts, do you also collect their text messages, social media posts, voice notes, WhatsApp messages, LinkedIn feeds and Substacks? Should we prioritise private documents over public? And if we decide to collect more social formats, how do we do it? Debates about authenticity and context evidently apply to social media feeds. And how do we protect the privacy of other individuals whose data might get caught in our collecting nets?

If you collect a writer’s digital manuscripts, do you also collect their text messages, social media posts, voice notes, WhatsApp messages, LinkedIn feeds and Substacks?

For the moment, the NLS is focusing on documents which could be considered digital equivalents of physical materials. And in 2024 they held a conference to engage the writing community in records management as a part of preserving their creative legacy. Chris acknowledged the potential risks, in terms of self-conscious curation and sanitisation of data. But these issues have always existed. And working together with current creatives seems both pragmatic and necessary in the face of so much data. As well as apposite in age when we’re urged to curate every aspect of ourselves and our lives.

As Chris and my conversation progressed the unanswerable questions piled up. And our view of the future became even hazier when we talked about how to exhibit digital collections.

What happens to exhibitions in an age of digital material?

Engaging visitors with papers and manuscripts can be challenging even when they’re as entertaining as Alasdair’s, but that challenge enters another level when the document is digital. Printed materials rarely have the same value for us as handwritten ones, and digital artefacts also challenge established notions of authenticity and originality. They may connect us to a writer’s thought processes - but they don’t necessarily connect us to our shared humanity.

There must be creative ways to transform a series of emails or a document with tracked changes into visually and emotionally engaging exhibits, but these will almost certainly impact the unmediated engagement with objects so valued by Chris and other archivists. Plus, most institutions aren’t endowed with the skills or spaces to create engaging digital exhibits. They’re legacy institutions in all senses – with shelves and display cases designed for physical rather than digital exhibits.

How can digital tools help us preserve humanity?

Discussing how to engage audiences with digital documents brought Chris and me back to the beginning of our conversation. And as it ended, I definitely felt overwhelmed by the challenges facing archives and archivists as they work to safeguard our future cultural heritage in the face of this new creative present.

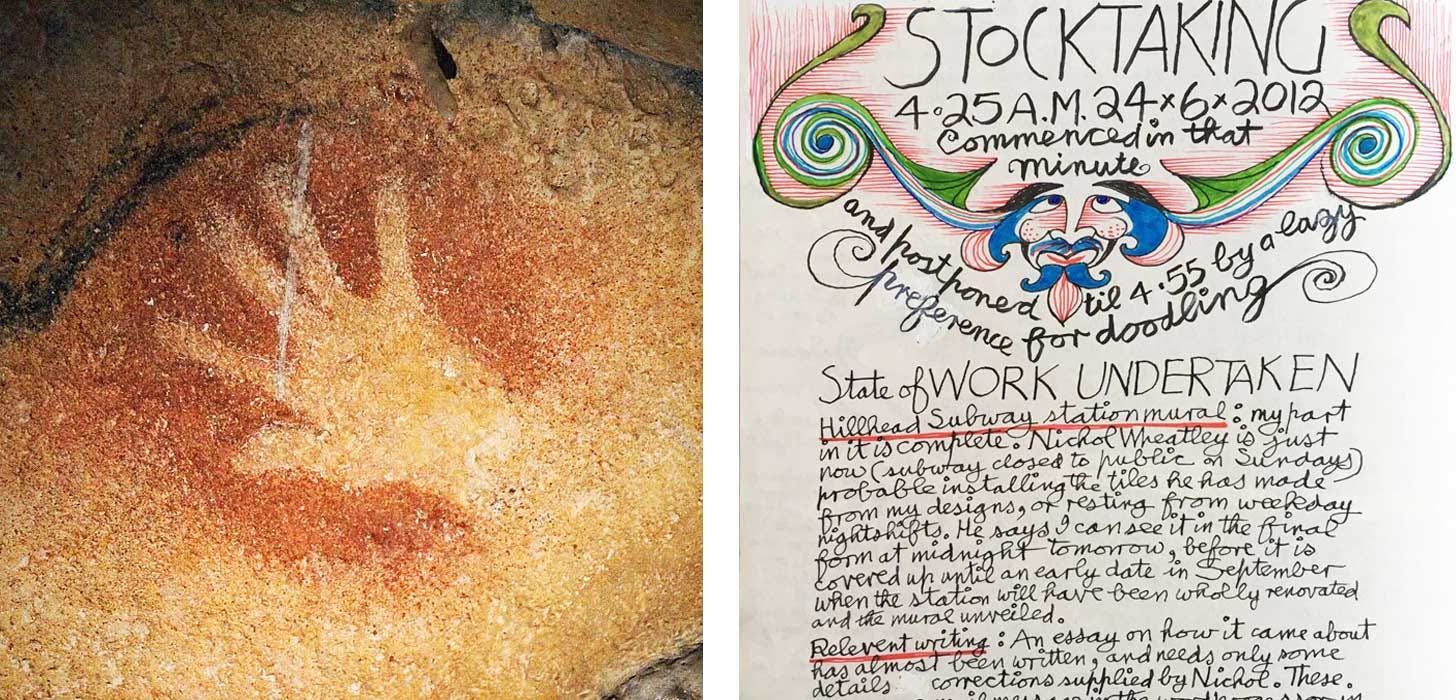

Reflecting on our conversation later I found myself thinking about some of our earliest creative artefacts – the hand prints on cave walls that can still instantly connect us to our ancestors because they look exactly like our own. For Chris and me, Alasdair’s handwritten documents and doodles offer a similarly immediate connection to their creator. And from this perspective, our digital future inevitably looks alienating and inhuman.

But then I found myself wondering whether there are other people for whom such physical artefacts won’t – or don’t – have the same emotional resonance? And if there are also digital alternatives that can offer a similarly human point of creative connection – if we know where to look for them? Because while digital tools may appear to de-humanise traditional archival artefacts such as documents and letters, they also open-up multiple other ways to record our creative selves.

Few things are more personal than our voices. And in the year before my uncle died, I made a series of informal and unscripted recordings with him that turned out to be gently informative and unexpectedly revealing.

Just like his writing, listening to these recordings instantly connects us to Alasdair’s unique voice and the ideas that interested him. So maybe as well as continuing to collect digital versions of traditional archival materials, now is the perfect time to start having some more existential conversations about our collective sense of culture in a digital age. Let’s consider what we value about it – and where we will we find our humanity in it.