Hi there Team Content,

The Wikimedia Universe holds a special place in my heart. Of all the third-party platforms that GLAMs can make themselves more visible on, Wikimedia is the only significant one that:

is not-for-profit

is run by a volunteer community

surfaces content mainly by human curation rather than algorithmic decision-making

Today we’ve got Martin Poulter back on Cultural Content. Martin is a Wikimedian in Residence for the Khalili Foundation. He previously wrote about how Wikipedia offers a great opportunity for preserving past exhibition content online.

In today’s article, Martin’s looking at another opportunity afforded by the Wikimedia universe for GLAMs; the Sum of All Paintings project….

We’ll cover

How to build a data set

The benefits of crowdsourcing

AI-assisted categorisation

Getting involved

Over to Martin…

An open alternative

As the web matures, an increasingly prominent way the public encounter art is through a cultural aggregator. Google Arts & Culture boasts over 100,000 artworks, Art UK has more than 300,000 paintings from collections around the country; and Europeana has 32 million images. By combining works from thousands of sources, aggregators enable entirely new explorations through art that would be impossible with a single collection.

Another aggregator is much less well-known but arguably more successful. The Sum of all Paintings (SoaP) is a project to collect at least basic data about every notable painting. At the time of writing it describes about a million paintings from more than 8,000 collections. It is part of Wikidata, one of the sites hosted by the non-profit Wikimedia Foundation. In some ways, SoaP is the opposite of Google Arts & Culture. Google gives you the finished cake, baked and iced. SoaP is a kitchen, stocked with eggs, flour, and other ingredients, that different people visit to see what they can make.

When looking at a professionally-curated product versus a collection of open-source tools wielded by “the crowd”, I think of Britannica or Encarta versus Wikipedia, and how the latter, despite its admitted flaws, became the dominant online reference source. This, in turn, is why I am confident that SoaP will have a part to play in cultural resource discovery a generation from now.

SoaP is an example of a WikiProject, a focussed effort by a mix of volunteers and professionals to improve data about a broad topic. Wikidata hosts similar efforts collecting data about other things held by cultural collections, such as manuscripts and astrolabes, and other creative outputs including performance art or video games.

Building the data set

The Sum of all Paintings dataset came about from a mix of formal partnerships, individual volunteer efforts, and repurposing of existing data. Some institutions have explicit partnerships with Wikimedia to freely share their catalogues. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met), for example, has shared 400,000 paintings and their metadata.

A small number of institutions including the Rijksmuseum and Tate have published open data sets with an explicitly free licence. Integrating these into the Wikidata model is far from trivial, but various software tools exist to help with it.

A large proportion of the other data comes from “scraping” the websites of cultural organisations with custom code. This process does not copy images or textual descriptions; those are by default protected by copyright. Adding a factual property (such as a painting’s year of creation) to Wikidata is legal because copyright affects the expression of facts, not the facts themselves.

Not all of the data are imported in bulk. Individual contributors can create or improve the representation of a painting in Wikidata’s interface. The hobbyists who do this are motivated by interest in a particular artist or culture, or in a category such as women artists or LGBTQ artists.

Uses by cultural organisations

Sharing on Wikidata can enable new ways to access art, including new front-ends for existing catalogues. It can also augment the data beyond what was in the original catalogue; two ways this can happen are cross-referencing with other information sources and crowdsourcing (getting the public to add data).

Wikidata is not just about art; it combines biographical, historical, scientific, and cultural information, with links to other sites and databases. Artist records can link to the Benezit biographical dictionary; concepts can link to the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus. Scientific concepts can link to appropriate databases. Hence we can get Benezit biographies of artists in the Ashmolean Museum. When, in a University of Oxford project, I described the botanical watercolours of Ferdinand Bauer, I identified the species of each plant. As a result, we can ask for paintings of plants in the Trifolium genus and get each species’ link in the Encyclopedia of Life.

An outstanding example of crowdsourcing is The Met’s process combining AI and the crowd to identify things depicted in its paintings. Painting images are fed into a Microsoft machine-learning model which suggests concepts it finds in the image. Through a Wikidata-driven app on mobile devices, human users verify those depictions with just a click (“Does this painting show a horse? Yes / No.”) The verified depiction statements are put into Wikidata and can potentially be harvested back into catalogues.

In my work as a Wikimedian In Residence, I have benefitted hugely from volunteer translations of Wikipedia articles. The same applies on Wikidata too. Facts are represented in Wikidata using numerical codes. Text labels are added on the fly, so the same fact can be rendered in English, Arabic, Uzbek or more than 300 other languages. Machine translation is not involved: translation of those text labels (such as artist names) into different languages is done by volunteers. As a result, basic information about artworks that I am entering in English is visible to a lot of different language communities who could not use the original catalogue.

Interfaces

To return to the baking analogy, some people use the kitchen to make a gluten-free muffin to fit their personal diet; others make a tiered cake that will be the centrepiece of a big event. Similarly, the SoaP dataset can answer niche questions or support ambitious software projects. Individual queries get answers in seconds that would take a very long time researching from the various collections’ websites:

Which artists are represented in the collections of both the Tate and the National Portrait Gallery?

Which paintings depict musical instruments and are in some way related to Hamburg?

Which works by Raphael are available in IIIF format? With just ten lines of code, Wikidata can identify works meeting a criterion (e.g. created by Raphael) and feed their IIIF links into a viewer.

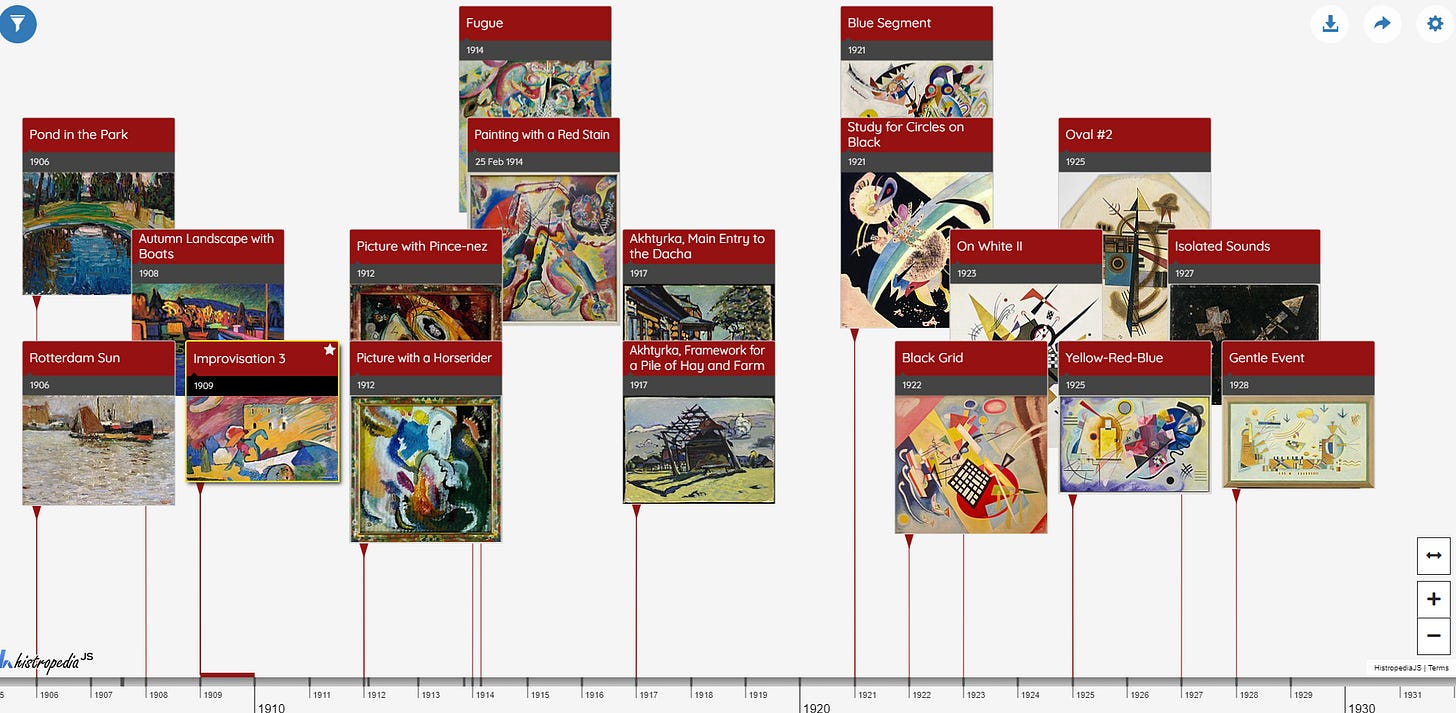

Given a query, Wikidata can generate data tables, image galleries, or interactive visualisations like maps and timelines. This is geeky stuff, out of reach of the general public, but programmers are using these features to build interfaces that are very easy to use.

Crotos was created at a hackathon and gives access to hundreds of thousands of artworks: those with both a representation in Wikidata and a high-res image in Wikimedia Commons. For each artwork, it has multiple links to further information, including a link to the collection’s catalogue entry if that is known to Wikidata. Open Art Browser was created as a student project and connects each artwork to many others through shared properties. iArt is another university-based project; it retrieves not just the painting you search for, but others that are thematically similar.

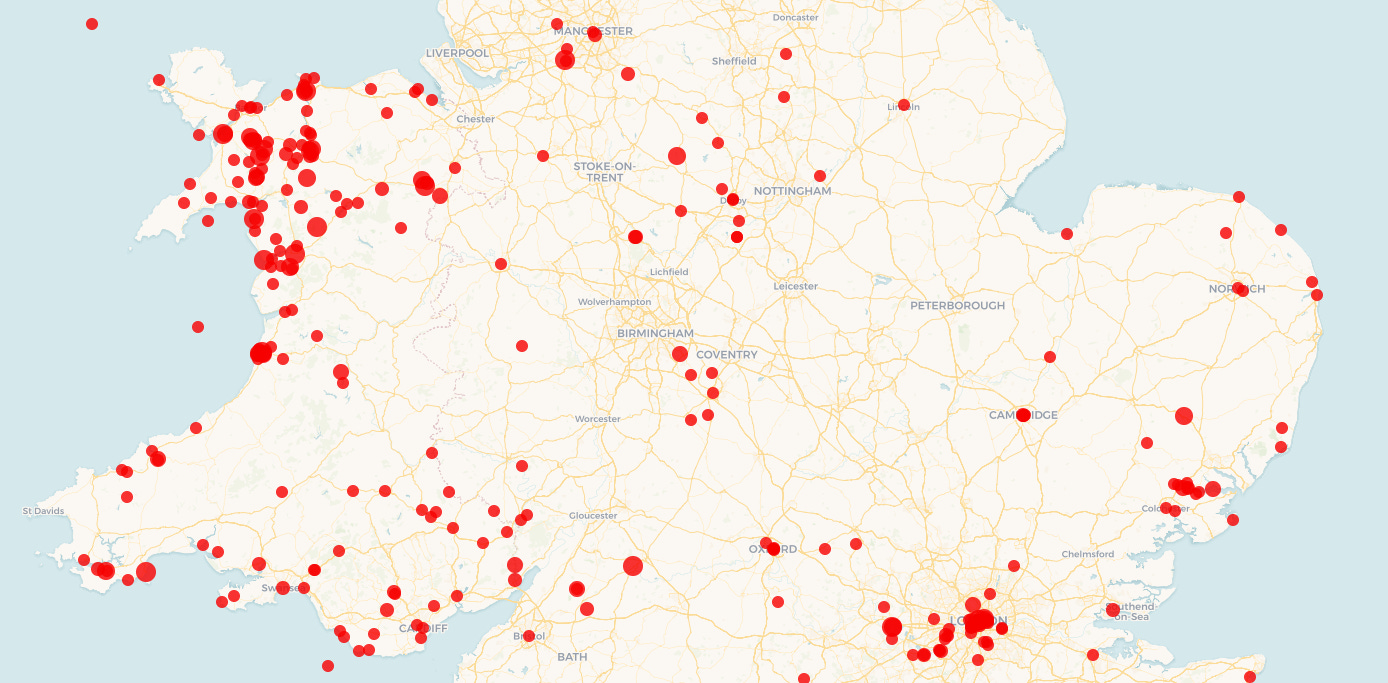

Painted Planet, built by a Dutch collective, is a map interface to landscape art. Each dot on the interactive map represents a painting of that location. Clicking it brings up a thumbnail with a link for more details. The National Library of Wales has described their landscape prints collection on Wikidata. So Painted Planet and similar Wikidata-driven maps show Wales covered in dots that show prints that depict each place.

Histropedia is an online tool that can accept queries from Wikidata and display them as gorgeous timelines. When an academic asked me for a timeline of Russian art from before, during and after the Russian Revolution, it was just minutes of work to make a colourful, interactive visualisation.

There are other kinds of interface to Wikidata, including natural-language or voice interfaces, with varying usability and reliability. New sites and applications are quick to develop because Wikidata has done the work of data modelling and collection. To let users search or browse many times more art than Google Arts & Culture, developers just have to build an interface. Wikidata’s openness, and the ease of creating data sets or code, make it an ideal basis for the next generation of innovative interfaces, whatever those turn out to be. It offers the same opportunities to any developer, whether corporate, student, or hobbyist.

Getting involved in the WikiProject

The WikiProject itself is a set of pages on the Wikidata site with guidance on how paintings and artists are described on Wikidata, including a discussion board (the “Talk” page).

Some of the WikiProject’s effort goes into creating database queries that track the quality of the data set: How many paintings lack a “creator” property? How many lack an inventory number? Dashboards, bringing together many such queries, are regularly updated by bots. These report how much Wikidata knows about a given collection or a given artist. One dashboard shows how many paintings from each collection are in the data set, and the data completeness of each. For instance, there are 5,713 paintings from the Royal Collection, three-quarters of which have a “material used” property while about a third have a “depicts” statement. Another dashboard shows how many paintings there are by each artist; the current top of the league is the Indian painter Nandalal Bose.

To edit directly on Wikidata, it’s advisable to log in so that your edits are attached to your profile. If you already have an account on Wikipedia, this will work on Wikidata too. To create an account, you just need an email address (which is kept private). If you want to join the WikiProject, you can add your username to the list of participants. It’s recommended to be open about who you are and your affiliation.

Search for the title of a well-known painting and you will see how it is represented in Wikidata, e.g. “Guernica”. You will see a list of “statements” each of which consists of a property (such as “material used” or “country of origin”) and a value (such as “paper” or “Ottoman Empire”). To add a painting that isn’t already there, click “Create a new item”, give a title or name, a very short description and start adding statements. A representation on Wikidata is called an “item” and every item should indicate what type of thing it represents. In the case of paintings, we do this with an “instance of” statement whose value is “painting”. In Wikidata, a surface artistically covered in paint has different representations from other things named “painting”, so be sure to choose the right sense of “painting”, the first one the interface suggests. Sophisticated auto-suggestion and auto-completion make adding statements a rapid process. Links to a painting’s catalogue entry can be added with the “described at URL” property or can be added to individual statements using “Reference URL”.

Institutional response

It will not be good news if the future of cultural resource discovery is a platform controlled by a mega-corporation; they have no incentive to link to GLAM institutions, pushing traffic away from their own site. Publicly-funded projects can create impressive aggregators, but are usually focused on one country or continent, not truly international or intercultural. Sum of all Paintings is truly a commons, combining the virtues of open access, open participation, and broad scope. Its downside is that it is messy and incomplete, permanently under construction.

An institution can completely ignore SoaP, just as it could in principle ignore the web or social media, but the key disadvantage is the same: you will be spoken about, but not part of the conversation. Institutions should at least take an interest in how their collections are represented in this data set. If you have self-portraits by women, or paintings of horses, or portraits of people playing musical instruments, can they be found using the tools mentioned in this article?

The most helpful thing a collection can do, for this and other data-sharing projects, is to structure its online catalogue to be friendly to incoming links. Ensure each artwork has its own public page, addressable via a simple URL. Remember that SoaP does not contain narrative descriptions of artworks, so foreground those narrative descriptions as the content that gives users a reason to visit the catalogue.

The next helpful thing is to create a spreadsheet of catalogue information describing paintings, with basic properties of each, including those links back to your online catalogue, put that file somewhere on the public web and, crucially, announce it on the WikiProject. The best value in terms of reuse will come from also sharing digital scans of the paintings on Wikimedia Commons. Even when this is not possible for copyright or other reasons, sharing the catalogue data will let all the SoaP-powered sites and apps know about your collections.

This article by Martin Poulter is released under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (CC-BY-SA 4.0).

Nice to know our work is appreciated Martin! Thanks for your insights!