Video games, internet culture and cultural heritage

Opportunities of video games to the cultural sector

Video games aren’t perhaps what immediately comes to mind when you think of digital content related to cultural heritage.

One of the differences is scale – companies like Nintendo, Ubisoft, EA generate billions of dollars of revenue per year, spend 100s of millions a year on marketing, and have tens of thousands of paid staff.

But I’m more interested in cultural perceptions of most sectors. There’s a tendency to think of museum visiting as a form of ‘high culture’, whilst gaming in your bedroom is ‘low culture’.

This distinction is unhelpful and untrue.

Before setting out to research this piece, I’d been peripherally aware of video games influencing popular culture, for instance in cinema releases (Mad Max / Lara Croft etc). But I hadn’t considered the amount of gaming content that – for example – dominates YouTube’s trending videos. This reminded me of how previous writers of this newsletter had referenced being influenced by video games:

Nik from the Tank Museum pointed out that their – very successful – YouTube and Patreon were originally inspired by his son’s obsession with YouTube Creator and Gamer “Unspeakable”.

Monterey Bay Aquarium talked about moving off X/Twitter and investing more time in platforms like Twitch and Discord (both online community platforms heavily used by gamers).

Gaming is hugely influential in popular consciousness. In 2008 an NPD poll found that 72% of the US population had played a game that year. In 2007 more Canadians could identify Super Mario than the current Canadian prime minister. Globally there are 3.2 billion gamers. Currently, the largest social media platform – Facebook – has less – 3 billion average monthly users. Video games occupy a huge space in popular consciousness for billions of people. To ignore them is to ignore a large and emotionally significant portion of the digital media landscape.

In this article, I look at:

Heritage references within video games

Museums creating their own games

Museums addressing existing video game fandoms

Opportunities

Barriers to GLAM/video game collaborations becoming more commonplace

Let’s get started…

Heritage references within video games

One of my favourite examples in this section is an Edinburgh art historian – Professor Glaire Anderson – who collaborated with Ubisoft for Assassin’s Creed and helped inform how they re-created medieval Baghdad:

As she says in the video (timestamp 20:17):

“When I look at the history of video games set in the mediaeval period, by default the setting is Northern Europe. That was one of the things that troubled me. I wanted players to have a more accurate understanding of the medieval period in a way that decenters the role that Northern Europe has in the public imagination of that time. I wanted them to play the game and understand medieval Islamic civilisation as a global phenomenon. These are the things I teach about. I wanted to reach a broader audience. I wanted to make this knowledge available to those who might not come across at the academy."

I love this quote. It touches on:

reaching a broader audience than would naturally come through ‘the academy’s’ doors (which might mean a university’s – but also a museum or library).

video games as a learning format that holds sway in popular consciousness.

learning by stealth (by visually taking in historically accurate references in the virtual world you are partaking in).

This isn’t a one-off for Assassin’s Creed. Each of their games recreates a historical world, and – in some cases – they have gone to great lengths to make these worlds (set in actual historical periods) as detailed as possible.

This meant that when Notre Dame was heavily damaged in the 2019 fire, Ubisoft had a model that had been built, brick by brick, from the real monument, in over 5,000 hours of research. After the fire, the company offered to share this model with the French government for free to aid restoration efforts. They also donated €0.5million to the restoration and made the game available to play for free for a limited time so that people could visit the virtual Notre Dame when the real monument was first undergoing restoration.

So as well as being significant to popular culture, video games can also help protect our cultural heritage, allow for the preservation of physical cultural heritage and widen engagement with actual historical monuments and civilisations.

Other types of games don’t recreate virtual historical words, but methodologically they teach users to think and use processes that mimic those of a curator;

“Many games gamify the collection/identification of real or fictional creature. For example, Animal Crossing involves collecting bugs, fish and fossils to fill a museum. Pokémon, the biggest media franchise in the world, and it’s basically biological recording!”

Glenn Roadley (Curator of Natural Science at the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery)

Animal Crossing also features real works of art in museums around the world. One gamer diligently visited all 43 real-life works of art featured in the game:

The Ashmolean have also created some of their artworks which you can import into Animal Crossing.

Museums creating their own games

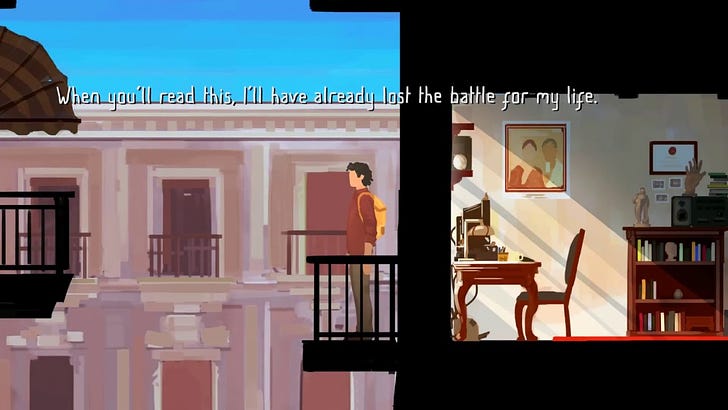

Many museums and heritage institutions have created in-browser or app-based games. For example, the National Archaeological Museum in Naples’s ‘Father and Son’ has been downloaded 5 million times since it launched in 2017:

“In the Strategic Plan of the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, one of the objectives was to increase the type of visitors to the museum through specific audience development activities. From my point of view, the creation of a video game allowed us to activate new forms of communication with new museum audiences.”

Professor Ludovico Solima, Chair in Management and Entrepreneurship of Cultural Organisations, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitalli”, Department of Economics

The Roman Baths created ‘Where’s my cloak?' in 2019. Tom Hardwidge – Founder of Tall Story Games – tells me, “The overall purpose of the game was to provide insights into the lives of real people who attended the Baths thousands of years ago.”

These two examples show that games can be strategic for museums in terms of:

broadening audiences.

simulating historical past/s.

Museums creating content referencing existing video games

One of the most interesting video games/ GLAM overlaps that I’ve seen has been from the Royal Armouries. Jonathan Ferguson is Keeper of Firearms & Artillery at the Armouries, but most commonly known as the internet’s ‘Firearms Expert’.

Jonathan stars in a series of ‘Expert Reacts’ YouTube videos which critique the historical accuracy of weapons used in video games.

“Evidently from the popularity of this series (videos getting hundreds of thousands, even millions of views), games can serve as a platform for discussions of historical accuracy” James Rice, MSc Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies Student, tells me.

The series has also been very useful for the Royal Armouries;

“His fame in this area has led to references to him within video games themselves. They’ve also led to popular memes. This has given a real human face to our museum and our feedback shows is one of the drivers for people coming to the museum today.

Authenticity and historical accuracy are hugely prized by a large segment of the gaming community. Jonathan is now working with games developers to improve their games and make tweaks to their weapons, so they are as authentic as possible. A Jonathan seal of approval is now seen as the gold standard for a video game. We’ve had games developers create videos on YouTube showing their delight that Jonathan has reviewed their weapons favourably.”

Florence Symington, Director of Brand and Audiences, Royal Armouries

In these cases we can see that engaging with existing gaming culture:

can help make collections and curatorial expertise contextually relevant to millions of users.

can help stimulate international commentary on historical accuracy.

can reposition museums as repositories to active commentators in popular culture.

The Armouries now have a dedicated 'consultancy' page on their website offering "curatorial consultancy and historical research services for film, game, media and commercial projects."

Adam Lamb, Head of Commercial and IP at the Armouries talks about the thinking behind this new service offering:

"We created it to bridge the gap between the museum and the film, tv and gaming industries – who have been hungry to use our content, but needed a dedicated team to work with at the museum who understand what the museum can offer and what the industry needs."

Opportunities

Video games as a format for lesson plans

The Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) has developed – ‘Game lessons’ – "a program of free lesson plans and professional development that help teachers use videogames in the classroom". Game-based learning is perhaps as unfamiliar to formal education in schools as it is in museums. Projects like these help break down the distinction between 'the academy' (in Glaire Anderson's terms) and popular culture.

Avenues for marginalised communities

Before getting too deep into this section it's worth stating that video games do not only cause social good:

The Wikipedia article 'sexism and video games' reports that 65% of female gamers have felt marginalised in gaming communities and that women are subject to three times the amount of derogatory abuse compared to men in online video game settings.

Playing daily violent video games has been linked to depression in teens.

However, there are instances of video games /culture sector collaborations that demonstrate how the medium can be used to promote diversity.

For example…

Bypassing internet censorship in Minecraft

Uncensored Library is a Minecraft server (which can also be downloaded locally) created by Reporters Without Borders. It provides a gateway to content (through the Minecraft server) which allows access to documents in countries that have been banned through internet censorship.

Video games as a means of simulating the experience of being black and trans

The game 'SHE KEEPS ME DAMN ALIVE' is an artistic installation by Danielle Braithwaite-Shirley. It takes the form of an arcade shooter game. However, your 'point and shoot' gameplay is interrupted along the way. As you make decisions in the game you are forced to stop and reflect on whether those same choices (to act or not to act in a given situation) would be sustainable if you were black and trans. In so doing, the artist forces participants to empathise with the black trans experience and question our complicity in maintaining unequal structures in our choice of action/inaction in given situations.

Barriers

But there's no point taking a purely starry-eyed approach to video games as a potential medium for the sector.

As much as there are opportunities, there are also huge barriers, some of which we can do very little about.

Cost

Video games are big business. We mentioned at the start of this piece the profits video game companies have. That goes hand in hand with very large teams working on design, research and development and the ability to create sophisticated virtual worlds and interactivity. Whilst there are instances where museums have developed games with millions of downloads (such as the Naples Archaeological Museum) the odds are stacked against you if your objective is to directly compete with the most popular games.

The disparities of scale and cost between the games industry and the culture sector are not things the cultural sector has any power to control. However, there are things as a sector we can be aware of…

A game should be treated like a learning or community program – it needs ongoing support, funding and marketing to keep it culturally active

In this article, we've explored how a good game can reach a wider audience than might come through the doors of a museum. Framed in that capacity, it's a tool for audience development. But unlike audience development programmes and community-building initiatives, it rarely has ongoing budget for tech updates, marketing and research and development. As long as this is the case, the success of these games will inevitably degrade over time.

Having a single vision for game-play

Ben Templeton, director of ThoughtDen; a small studio behind arts/culture games like Magic Tate Ball and Total Darkness, talks about some of the pitfalls he experiences working with clients in the early stages of a video game brief:

"It's easy to think about games being pitched on a spectrum of 'having fun' to 'learning'. But this is wrong. Learning is inherently fun."

He goes on;

"The best games I've worked on in the sector are those where you align learning content with the mechanics of the game. Where getting better at the game means you necessarily understand the content. Or when the game-winning strategy is to have a better understanding of learning outcomes... The moment when they marry is beautiful to behold."

An experiential outcome can be more powerful than fact retention

Ben warns against pitching game learning outcomes that are overly prescriptive on fact retention. For example in a game about Jewish persecution in World War Two, you might not remember the date of the start of the war, but you're likely to come away with a holistic understanding of the experience of being persecuted and some of the specifics of what that looked like, and that is surely more important and powerful than the exact date it happened.

Conclusion

Video games are difficult, some have problematic elements (c.f. previous notes on misogyny and depression).

So why should we bother?

Video games are just another medium. Social media, and internet culture in general have the same problems with misogyny, racism, transphobia, and depression in teens (we could also add inflaming bi-partisan politics).

Creating video games is also difficult and expensive.

All that having been said, they're also unique in terms of

The technological ability to create immersive worlds, including recreating historical pasts and bringing to popular consciousness objects, monuments and worlds from lesser-known parts of history.

Imaginative storytelling. Similar to the above there are few media I've come across that create such visceral narratives.

The ability to give users agency to direct their learning. This is the participatory museum writ large!

International fandom and online buzz (spilling across YouTube and Twitch) – gaming seems such an important part of internet culture that being able to converse within game-specific memes, content and trends allows you to see how your collections might link to gaming culture.

Gaming allows us to build online communities, develop immersive worlds through storytelling, and make visitors more active participants in our storytelling. They encourage learning and exploration through play. They allow us to conceptualise and interact with three-dimensional objects and civilisations. This seems to touch on lots of aspects of museum engagement thinking.

Not everyone will get a positive learning experience from an object label in a physical museum. Not everyone will feel welcome in a museum. Video games aren’t an easy format to crack but it feels worth the effort to investigate the possibilities.

In the words of ACMI CEO and Director Seb Chan “We need our cultural organisations to be more than just consumers of technology, we need an engaged relationship with the technologies and infrastructure we and artists work with” – video games are one of the significant formats that can play out on.

That’s it for this week.

This article originally came about as a conversation in a pub with James Rice (MSc Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies Student), and would not have happened without him and his enthusiasm for, and knowledge of, both gaming and heritage. The Museum Computer Group Discussion List generated 77 email responses to my initial call out for information, thank you to everyone who helped shape and participate in this conversation.

As well as those mentioned in the post I should name-check Ed Bankes, Ellie Field, Simon Jones, Chris Unitt and Drew Wilkins for pointing me to examples that I reference in this finished piece, and/or generally making the piece better.