Picture this: your museum/gallery/heritage institution has an online blog. It was probably set up some time ago. When the blog was set up the idea was that readers would arrive on the blog homepage fairly regularly and read the latest articles coming in.

Times have changed. And the way we present articles hasn’t enormously.

There are two main ways most culture sector article sections haven’t kept step with changing user behaviour:

1. Most web articles are ordered chronologically by the most recently published post. However, let’s say there’s a current exhibition on fashion. All the most recent articles are to do with fashion. Let’s say your collections are much broader than just fashion; covering natural history and fine art also. Suppose someone arrives on your blog interested in rocks, it’s quite difficult for them to find or surface content related to their interests.

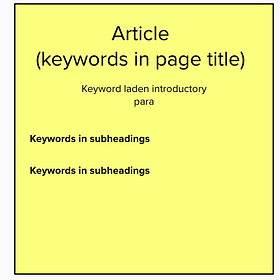

2. Today, the main way people access blogs and articles is via search. Or at least these pages have the most opportunity to bring in search traffic. Articles are the pages on your site that contain the most words. And – on a very simplistic level – Google is trying to match the words someone enters into a search bar with the words on webpages.

TL;DR we’ve built articles based on a model where someone regularly visits your blog homepage and reads updates as they come in. In reality today, visits are much more serendipitous. People will come directly from search with no context on who you are, what related content you have to this post and how this sits amongst your wider collections.

This is the situation the Royal Mint Museum were in. They’d moved blog content from a series of previous CMS’s into one central website. But the underlying structure of the content hadn’t changed enormously. Articles were structured under editorial categories like ‘curator’s corner’ and ‘guest articles’, but there was no way of sorting content by period, or geography. This made it very difficult for new users landing on the site to navigate to articles relevant to their interests.

In this article, I’ll take you through the three-step method I use in situations like this to restructure editorial content to improve usability and SEO.

Step 1: Research existing content and user behaviour

Analyse current performance

There are a number of tools you can use to analyse your current performance:

GA4 will tell you which pages on your site are responsible for the most search traffic

Google Search Console will tell you what queries are giving you the most search traffic

However, only paid tools will tell you:

Which pages are giving you the most traffic from search (and for which keyword/s)

How competitive the keywords are that you’re getting traffic from

What the search volume is for terms that are relevant to your organisation that you’re not currently using, and how this stacks up against the keywords and topics of your published articles

How much traffic you’re getting from Google images, including images that illustrate articles

Identify relevant keywords

Use paid keyword research tools such as SEMrush to discover what people are searching for related to your museum’s collections and expertise. This will help you:

Identify which keywords and pages are most effective at driving traffic from search currently

Where the gaps are; for instance lots of searches related to something you have expertise in, but currently no articles or content to meet that interest

Identifying relevant high-opportunity keywords and topics is not straightforward – particularly if your collection area is vast. It's not always easy to think of topics you're not yet dominating for. Start with keywords for topics and collections areas you have strengths in. I often look at the kinds of terms or objects visitors are frequently mentioning on TripAdvisor or look at the floor plan and collections online to give me a corpus of potential keywords to evaluate. You'll need a tool like SEMrush that can tell you how widely searched that term is, and what the existing competition ('keyword difficulty') for a given term is.

These two datapoints should give you the best data available on what the current jewels in your SEO crown are amongst your article base, and where your gaps are. By looking at the types of popular queries coming up (that are also relevant to you), you can start grouping topics and subtopics, identifying ideas for new articles.

There’s more information on how to do step 1 in this article, under the heading ‘So how can you rearchitect your editorial to make it search friendly?’:

At the end of the research phase (step 1) you should be able to start developing some topic clusters and potential ways of grouping different categories of content.

Step 2: Experiment with content structure

The patterns that emerge from step 1 are unlikely at this stage to be fully comprehensive or even - perhaps - stand up to curatorial scrutiny. This is where you need to mix:

your knowledge of the keywords people are searching for, with:

their taxonomic and subject matter knowledge

I’ve found an open card sorting exercise a useful technique for doing this

Reframing content organization through card sorting

Here’s a screenshot from a remote card-sorting tool, in this case Lyssna, but many other online tools exist.

For this exercise, you will want to prepare:

A list of the 50 most viewed pages related to your collections. Make each page title into its own ‘card’.

A remote card sorting tool (like Lyssna or Useberry).

Five knowledgeable volunteers with diverse perspectives on the collections.

Within the exercise, participants will drag and drop individual page titles into categories and supply names for these categories. The data from your five participants will provide you with a series of options for how to slice and dice collections content that is factually correct.

I prefer doing card sorting remotely as it’s more similar to the behaviour of an actual web browser. The alternative is in-person card sorting. However, I find that in-person card sorting biases in favour of the most extroverted and/or senior members of the team. But introverts and extroverts browse websites. Remote card sorting removes the bias and captures a greater diversity of possible categorisation structures.

Don’t feel you need to use any of these structures as law. It’s interesting if lots of the participants individually chose similar ways of grouping content. But you need to overlay your knowledge of terms people are using outside of museum staff onto their understanding of logical groupings. This will help you to arrive at possible structures that are both accurate and effective in search.

Validate new structures with tree testing

At this point in the process you will hopefully:

Have an idea of where the biggest opportunities are, in terms of topics and expertise that your museum has that are widely searched for, but not covered at the moment on your blog – and where perhaps these topics might sit in an overarching structure

Have a sense of how topics breakdown; where are there distinct clusters of interest and topics in different groups and subgroups?

How your existing high-performing article content might fit into possible new topic-based categorisations

But there’s a difference between creating a series of categories that work in the abstract, or even amongst specialists, and what works in the real world. So it’s important to test-drive these potential structures before baking them in

To do this, I tend to use tree testing.

A ‘tree test’ is a type of research study. It allows you to ask participants where they would ‘expect’ to find certain content on the website. To make their choice, they can browse categories of content

This shows part of an actual tree test from the Royal Mint Museum

To do this, you’ll need:

A navigation ‘tree’ based on your current website and at least one other alternative to A/B test against

A series of questions that force users to go down tree nodes which expose variations between your A/B test variants

A software tool like Useberry to randomly serve participants one of several navigation systems.

There’s more information about tree testing here:

Once you get the data back from this test you can compare how easily participants found content in your current editorial system versus the new categorisation systems you’ve proposed.

Step 3: Analyze and implement findings

To arrive at a final navigation structure for your articles you want to combine the insights you’ve gleaned from all your research so far, including:

Keywords driving the most search traffic to your articles so far (from your SEMRush analysis in the Research phase)

Terms people are searching for in Google relating to your collections and expertise (from your SEMRush analysis in the Research phase)

Staff card-sorting data of different ways of categorising collections pages

User data on how intuitive new possible editorial structures are compared to your existing site (from tree testing).

There’s no more data to gather at this point. Time to start analysing. Try and synthesise the findings from all of the above to arrive at a new navigational structure that stands up logically, uses terms people search for, and performs well for findability. Make sure the categories you choose not only reflect staff-preferences but also align with how users search for content related to your museum.

And that’s it! This is exactly the kind of knotty data-plus-creativity challenge I really enjoy.

Wishing you a marvellous 2025. To making content more effective 🥂